After attending the recent launch of the Regional Lionfish Strategy at the International Coral Reef Initiative general meeting one month earlier, I was excited about taking the next step in collaborative efforts to control invasive lionfish. This time, it involved travelling to the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute’s (GCFI) 66th annual conference in Corpus Christi, Texas, where The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) were convening a session and special workshop specifically on lionfish ecology and management.

An invasive species in the tropical western Atlantic, lionfish have a voracious appetite for juvenile fish, and reproduce every four days. Their rapidly expanding population poses a serious threat to the continued health of Belize’s coral reefs and fisheries.

Lionfish in the Market – Challenges and Opportunities

The workshop, led by Dr. James Morris of NOAA and Lad Akins of REEF, took place on the first day of the conference and brought together 30 leaders in invasive lionfish research and management from around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. It was a wonderful feeling to look around the room filled with people and knowing that everyone was dedicated to realising the same goals.

Much of the initial discussion centred on ciguatera toxicity and the potential for lionfish to be a vector for Ciguatera Fish Poisoning (CFP). I was pleased to hear from the experts that there is no cause for alarm – ciguatera is found in 400 species of fish, from parrotfish to barracuda, meaning that there is a small risk any time we eat any tropical seafood. The risk factor can change dramatically depending on where the fish was caught (download Blue Ventures’ Ciguatera, CFP and lionfish PDF for more information).

David Johnson, founder and CEO of Traditional Fisheries, presents his prototype lionfish smart trap; he plans for the trap to learn to recognise the silhouette of a lionfish, thereby limiting bycatch. The benefits of developing a lionfish-specific trap is that it could be deployed beyond recreational dive limits, where lionfish are bigger and more abundant. (Photo credit: Traditional Fisheries)

We then looked at existing and potential market interventions for lionfish population suppression. The majority of efforts thus far have been focused on the use of fillet meat in high-end restaurants. Although important, it is not the whole solution, as demand through this market is for large fillets – typically from a fish that is at least 30 cm long.

With lionfish reproducing every four days, releasing 20,000 eggs per spawning event, and becoming sexually mature at as little as 10 cm long, 20 cm worth of growth is too long to wait. Building a market that utilises smaller individuals is essential to ensure that market interventions are effective.

One solution is to identify food products that do not require large fillets – amongst others, reconstituted fish products, fish meal and cat food have been nominated. The domestic market throughout Central America and the Caribbean has the potential to utilise small lionfish in local dishes such as ceviche and empanadas.

A delicious lionfish ceviche, prepared by Travis Riggs, founder of Sea2Table, was served to the workshop participants. (Photo credit: Travis Riggs)

Thinking slightly more outside the box, there is potential value in the lionfish spines themselves. Independent artisans in Belize (Placencia’s Treasure Box and Palovi Baezar, from Punta Gorda) are already producing prototypes of lionfish jewellery, and some online shops sell lionfish spine earrings.

But there remained one market for lionfish that no one in the room had explored. Despite the fact that the aquarium trade is the origin of the invasion, 60,000 juvenile lionfish are still being imported from the Indo-Pacific to the USA every year to meet its demand. Not only could these imported lionfish supplement the gene pool of the invasive population, but the consequence of removing so many lionfish from their native range – where they are relatively scarce – is unknown.

Harvesting juvenile lionfish from the Caribbean to supply the aquarium trade could have, at worst, a neutral effect (if the fish were subsequently re-released), but at best, a positive one through providing economic value to those lionfish in high-risk ciguatera areas. Mechanisms to prevent the use of destructive fishing techniques, such as cyanide fishing, must be proactively applied.

There was absolute consensus amongst the group that the import of invasive lionfish from their native ranges has to stop.

At the end of the workshop, Jen and Travis Riggs of Sea2Table, a sustainable seafood distributor linking fishers and chefs, discuss the possibilities for listing Belizean lionfish on his website. (Photo credit: Traditional Fisheries)

Lionfish Biology, Monitoring and Management

On day two, the main room filled to capacity as the GCFI attendees eagerly awaited the lionfish monitoring and management session, chaired by Dr. James Morris (NOAA) and Lad Akins (REEF).

From ciguatera, through market development, to stomach contents analysis and population structure, all the talks drove home just how big of a problem invasive lionfish has become. Christie Wilcox, currently undertaking a PhD that investigates the evolution of the venom found in lionfish, scorpionfish and stonefish, live tweeted throughout the session. This has now been storified to explain (in 140 characters or less) each presenter’s key findings. Interestingly, Christie’s research has taken a turn to investigating the relationship between lionfish venom and ciguatera, and suggests that the venom may cause a false positive in ciguatera toxicity tests.

Jen’s presentation described the lessons learned from Blue Ventures’ lionfish market development project in Belize, and discussed the obstacles and opportunities for the industry looking forwards. (Photo Credit: Martin Russell)

That evening, the poster session was held, with a disproportionately large number presenting issues related to invasive lionfish. One interesting poster by Adam Nardelli demonstrated the economic gain for a community hosting a lionfish derby; Joanna Pitt’s poster described efforts to develop a lionfish-specific trap in Bermuda, where market development is hindered by lionfish’s unreliability to take bait on a line, combined with the facts that fishers don’t freedive and spearfishing is illegal.

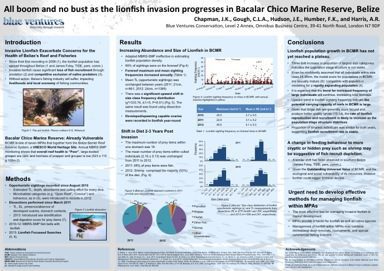

The structure of the lionfish population in Bacalar Chico, Belize, indicates that it is undergoing a rapid growth phase. The actual carrying capacity of the area is uncertain, but high sighting frequencies, almost 50 in one hour of SCUBA diving, indicate that the worst is yet to come. (Photo Credit: Blue Ventures. All rights reserved)

The following three days were occupied by talks on reef fish spawning aggregations, conch and lobster fisheries, and marine protected area management, as well as a visit to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Marine Development Centre and Padre Island – the longest undeveloped barrier island in the world.

But by far the greatest highlight was the opportunity to meet and discuss solutions to an issue that affects the entire Caribbean. The contacts made and lessons learned will help us to bring invasive lionfish research and management in Belize to the next level.

(L-R) Dr. Stephanie Green (Oregon State University), Alexander Bogdanoff (NOAA), Dr. James Morris Jr. (NOAA) and Jennifer Chapman (Blue Ventures) on the windy beach at Padre Island, TX, USA.